Optical Micro-Particle Shield Array (OMPSA) for Advanced Spacecraft Protection in Orbital and Deep-Space Environments

Table of Contents

Read DETAIL.md for an extended analysis of this proposed system.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Core Concept

- Radiation Mitigation

- Ballistic Protection

- System Requirements and Control

- Engineering Challenges

- Potential Applications

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

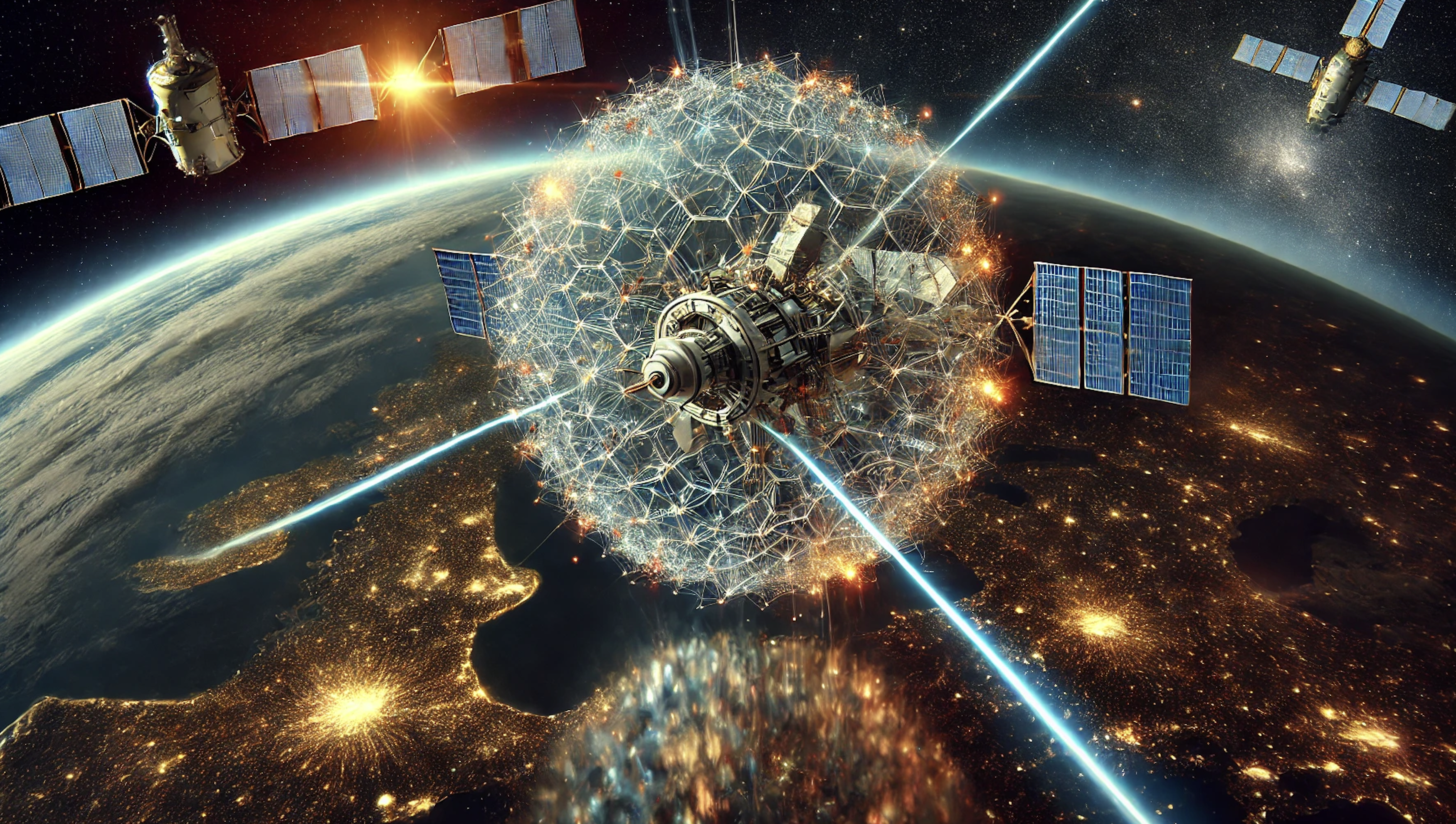

The Optical Micro-Particle Shield Array (OMPSA) is a concept that leverages holographic optical trapping to form a dynamic, self-sustaining shell of tiny particles around a spacecraft. By placing thousands or even millions of laser-controlled “optical tweezers” in a three-dimensional lattice, OMPSA defends against two major hazards of space travel: ballistic impacts from debris or micrometeoroids, and high-intensity electromagnetic radiation. Traditional shields—metallic hulls, layered Whipple bumpers, or thick composite plates—often force designers to accept steep mass and volume penalties. OMPSA aims for an adaptive, potentially lighter-weight strategy, capable of continuous updating to reflect changes in orbital debris fields, solar flare intensities, or other factors.

Although rooted in decades-old laboratory research on laser trapping of glass beads or biological cells, OMPSA extends these techniques to spacecraft scales. Within this framework, an array of high-power lasers and spatial light modulators (SLMs) maintain a spherical cloud of microparticles or nano-lattices a short distance from the spacecraft hull. This cloud helps break up debris at collision velocities of ~7 km/s and scatter or absorb harmful radiation. Below is a concise overview of OMPSA’s main principles, from the fundamental physics involved to potential mission applications.

Core Concept

Holographic Optical Trapping

OMPSA depends on optical tweezers: focused laser beams that exert gradient and scattering forces on particles. In typical lab experiments, a single trap confines one or two particles. By contrast, OMPSA requires an extended series of traps, encompassing enough microparticles to form a protective bubble. Modern SLMs let us shape the phase front of a laser beam, dividing it into multiple high-intensity nodes. Each node is effectively a stable pocket for a dielectric particle.

A control system adjusts these phase patterns as debris inflicts local damage, or if the spacecraft maneuvers. If a segment of the cloud is lost, the SLM software calculates a new hologram to recapture replacement particles from an onboard reservoir, quickly repairing the shell.

Particle Choice

Particles must exhibit:

- High refractive index (e.g., silica or sapphire) to ensure strong trapping forces at moderate laser intensity.

- Durability and radiation resistance, especially if operating for months or years. Ceramic or doped glass can remain stable under extreme UV or cosmic rays.

- Potential for advanced coatings, such as thin layers of metals that reflect a larger portion of incident light, or doping with heavy elements like bismuth or lead for partial X-ray/gamma attenuation.

- Electrostatic stability, using mild charges or slightly conductive surfaces to prevent clumping.

Ideally, a spacecraft might carry multiple varieties of particles—some optimized for ballistic mitigation (robust, mid-sized spheres) and others optimized for radiation reflection or absorption (metal-coated or doping-laden).

Radiation Mitigation

Scattering and Reflection

Space radiation spans everything from ultraviolet photons to energetic cosmic rays. At moderate energies (UV and visible bands), scattering by small particles effectively reduces flux intensity. Metal or ceramic coatings further reflect incident EM waves, trimming total exposure. If thousands of reflective particles lie in the path, the combined effect becomes nontrivial for typical solar flux or intermittent flares.

Resonance-Based Approaches

Leading-edge visions of OMPSA propose sub-wavelength lattices or even atom-scale arrays that could, in principle, enforce photonic bandgaps or wave interference phenomena. By precisely spacing trapped atoms or nanoparticles, one might selectively “block” certain frequencies (e.g., targeted X-ray lines from solar bursts). Though extremely challenging, it resembles the concept of metamaterials used in terrestrial labs. With advanced real-time sensing, a future OMPSA might measure incoming wavefronts and attempt partial destructive interference. While not yet practical at large scales, smaller demonstrations in specialized frequency ranges might appear within the next decades.

Constraints and Future Synergies

Some cosmic radiation (like ultra-relativistic cosmic rays) is too energetic to be easily neutralized by wave phenomena or thin layers of microparticles. Hence, many proposals suggest combining OMPSA with magnetoplasma fields, generating an artificial magnetosphere to deflect charged particles. The synergy could bring major improvements over purely static shields, especially for long-duration missions beyond Earth’s protective magnetosphere.

Ballistic Protection

Fragmentation of Debris

In orbital environments, even a tiny bolt fragment can impart catastrophic damage at multi-km/s speeds. Rather than absorbing the impact on a single metal plate, OMPSA uses a particle cloud to break the projectile into smaller fragments, dispersing momentum across multiple collisions. After the debris has been fragmented and slowed, the spacecraft’s underlying hull faces a significantly reduced threat.

Cloud Maintenance

High-speed debris inevitably knocks some particles out of their traps. Real-time cameras or LIDAR sensors detect these localized losses. The system re-activates or repositions traps, pulling in fresh microparticles from a reservoir. This self-healing nature allows OMPSA to sustain performance over long operational periods, in contrast to passive shields that remain damaged after a collision event.

System Requirements and Control

Power Sources

- Advanced Solar Arrays: Multi-junction panels can supply kilowatts of power, suitable for near-Earth missions.

- Nuclear Options: RTGs or compact fission reactors may be essential for deep-space probes or outer-planet missions, where sunlight is scarce.

- Thermal Management: Both the lasers and the trapped particles can generate and absorb heat, necessitating radiators, coolant loops, and robust thermal design.

Real-Time Feedback

A suite of sensors—ranging from cameras for shell integrity to spectrometers for radiation flux—feeds data into an AI/ML-driven control system. This system adjusts the SLM phase patterns, dispensing new particles, and altering trap density. Potentially, it can also tune advanced wave-interference modes if that technology matures, focusing on blocking or scattering urgent radiation bands.

Engineering Challenges

Thermal Load Management

Megawatts or even kilowatts of continuous laser output produce substantial heat. Active cooling lines must pass near the SLMs, laser diodes, and final beam combiners, channeling residual heat to radiative surfaces. Ensuring that the spacecraft’s power and thermal budgets can handle these demands is a prime design constraint.

Electrostatics

Particles can accumulate stray charges from solar winds or local plasma. Slight net charges help maintain spacing, but large imbalances risk partial shell collapse. Ion/electron beams or conductive coatings minimize random clumping or electric-field disruptions.

Computational Demands

Generating thousands of discrete traps at once, updating them multiple times per second to handle collisions or orientation shifts, involves substantial parallel processing. GPU-based clusters or specialized optical computing can expedite hologram calculations. For wave-interference approaches, an additional layer of real-time, frequency-specific computations is needed.

Potential Applications

LEO and GEO Stations

Space stations in crowded orbits face an increasing risk of collisions with debris. OMPSA could scale coverage up or down as debris forecasts shift, acting as a reconfigurable, mass-efficient defensive bubble. During solar events, a shell of reflective microparticles might also mitigate acute UV or X-ray influx.

Deep-Space Vessels

Missions beyond Earth’s magnetosphere encounter heightened cosmic rays and micrometeoroids. OMPSA’s capacity for self-replenishment and dynamic wave manipulation could extend mission durations or protect crew compartments. In the future, local regolith might be refined into microparticles, reducing Earth-based resupply.

Satellite Constellations

Mega-constellations for broadband or Earth observation operate in debris-prone altitudes. Equipping satellites with partial OMPSA shells may extend satellite lifetimes and reduce the need for frequent orbital maneuvering to dodge fragments, thus conserving fuel and simplifying cluster management.

Conclusion

OMPSA envisions a transformative approach to spacecraft shielding. By merging high-power lasers, advanced holographic phase control, and carefully optimized microparticles, it provides a flexible, self-healing shield that addresses both ballistic collisions and electromagnetic hazards. While current technological hurdles—from thermal management to sub-wavelength wave-interference precision—are nontrivial, ongoing advances in photonics, AI-driven feedback, and in-space manufacturing hint that OMPSA’s dynamic defense could soon be within reach.

Ultimately, this concept invites a shift from static, mass-heavy barriers toward active, reconfigurable shells that adapt to real-time conditions. If proven feasible, OMPSA would yield profound implications for future Earth-orbiting stations, deep-space exploration missions, and large satellite constellations, potentially reshaping how we protect critical assets amidst a rapidly maturing—and increasingly crowded—space environment.

References

- Ashkin, A. et al. (1986). Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Optics Letters.

- Dholakia, K., & Zemánek, P. (2010). Colloquium: Gripped by light: Optical binding. Reviews of Modern Physics.

- Grier, D. G. (2003). A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature.

- Smalley, D. et al. (2018). A photophoretic-trap volumetric display. Nature.

- Pichard, G. et al. (2024). Rearrangement of single atoms in optical tweezer arrays. arXiv preprint.

- Novotny, L., & Hecht, B. (2012). Principles of Nano-Optics. Cambridge University Press.

- Chang, D. E., et al. (2020). Quantum optics of ultracold atoms in optical lattices: toward X-ray regime metamaterial arrays. Physical Review Letters.

- Madani, H. et al. (2023). Machine-learning hologram optimization for dynamic multi-beam optical tweezers. Optical Engineering.